For me, no book is worth devoting a year of my life to

writing and editing unless it speaks to issues I hold dear.

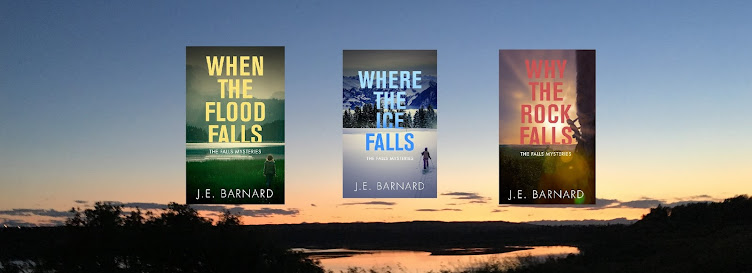

Where the Ice Falls is the second in The Falls Mysteries. It takes place 6 months later than the first and – amid the crimes and the Christmas crush

in malls and markets – deals with some recurring themes as well as new ones:

step-parenting, medical assistance in dying (known as MAID in Canada), and whether the

human spirit can communicate from beyond the grave.

Where the Ice Falls is the second in The Falls Mysteries. It takes place 6 months later than the first and – amid the crimes and the Christmas crush

in malls and markets – deals with some recurring themes as well as new ones:

step-parenting, medical assistance in dying (known as MAID in Canada), and whether the

human spirit can communicate from beyond the grave.

When the Flood Falls touched on domestic violence, first-responder

PTSD, financial precariousness for women, and chronic illness as well as topics

even more closely related to the string of crimes (trying to avoid spoilers).

Today I’m going to talk about MAID, but first some

orientation to the world of The Falls Mysteries.

Like Flood, Ice takes for its geography the landscapes

of the Rocky Mountain

foothills west of Calgary.

Familiar locations include the hamlet of Bragg Creek in the south and the town of Cochrane further north. The story moves further west as well, grazing the Stoney-Nakoda First

Nation and the hamlet of Waiparous before penetrating the near-trackless

forests of the Ghost River Wilderness Area. There's a purely fictional ski resort carved onto the northeastern shoulder of Blackrock Mountain, should you wish to examine the region on satellite.

Like Flood, Ice takes for its geography the landscapes

of the Rocky Mountain

foothills west of Calgary.

Familiar locations include the hamlet of Bragg Creek in the south and the town of Cochrane further north. The story moves further west as well, grazing the Stoney-Nakoda First

Nation and the hamlet of Waiparous before penetrating the near-trackless

forests of the Ghost River Wilderness Area. There's a purely fictional ski resort carved onto the northeastern shoulder of Blackrock Mountain, should you wish to examine the region on satellite.

The opening of Ice in

mid-December finds our three Bragg Creek women not only surrounded by snow but

in slightly altered personal circumstances than they were at the start of

‘Flood’:

Lacey – still working part-time for Wayne, still waiting for

Dan to sell their house in Langley, BC, still living at Dee’s where she’s doing

all the driving and most of the household chores; she’s even learning to cook!

Dee – slowly recovering

from her devastating injuries of last summer and trying to re-start a career

that barely resembles her old job as a high-powered real estate vice-president

so she can keep on paying the two mortgages on her lovely log chalet.

Jan – still has ME/CFS and is trying a life hack she heard

about in an online support group: going someplace warmer through the coldest

month of the Canadian foothills’ winter. If this works, she'll go into next summer less depleted from trying to make an energy-starved body run both its heater and its immune system at the same time.

There are new women characters too: Dee’s

artist mother, Loreena; Zoe, a mom/stepmom/administrative trouble-shooter for

oil companies; her spirited daughter Lizi, who tumbles over the first body

almost the instant she and her mother appear on the page; Zoe’s current boss’s

ex-wife Arliss; and an acerbic accountant/cross-country ski instructor

named Marcia. Each of those women has their own challenges to face, but today

we’ll stick with Lacey and Dee.

Into Lacey and Dee’s recovery-focused life comes a new

complication: Dee’s mother’s cancer is back,

and it’s terminal, and she wants to spend one last Christmas with her only

daughter. It’s going to be enough of a challenge to add another invalid (and

her nurse/friend/travel companion) to the log house but Loreena soon springs

another complication: she wants Dee’s blessing

on her application for Medical Assistance in Dying.

Into Lacey and Dee’s recovery-focused life comes a new

complication: Dee’s mother’s cancer is back,

and it’s terminal, and she wants to spend one last Christmas with her only

daughter. It’s going to be enough of a challenge to add another invalid (and

her nurse/friend/travel companion) to the log house but Loreena soon springs

another complication: she wants Dee’s blessing

on her application for Medical Assistance in Dying.Truth be told, when I first began planning this book, assisted dying was not even on the Canadian government’s radar. My father, however, had always wanted assisted dying and never been hesitant about talking to me about his determination not to linger in a state of advanced physical or mental decrepitude. Assisted dying was popping up on my radar every family holiday, whether I wanted to talk about it or not, and naturally I paid close attention to the gradually changing attitudes in Canadian society and governance. By the time I was ready to write what was sure to be an emotionally challenging book, Canada’s first Medical Assistance in Dying law was already passed.

What I didn’t know then – what my father didn’t know then – was that he was terminally ill already. Much of my writing life that year was punctuated by phone calls home to see how he was feeling as his physical body gave out bit by bit. His mind was still strong and he was determined to have all his affairs organized before he went. He was enjoying his Facebook time every day, often surfing while asking me how my book was coming. His impending death, and the logistics of applying, were always there in the background but rarely came to the fore because we both knew how he was going. We laughed often, and enjoyed reading the same books in our different provinces.

Here we are holding Tim Hallinan's 'In Fields Where They Lay', a Christmas crime tale that Tim graciously sent us autographed copies of. It was to be our final shared read. Dad always enjoyed a good killing, and he said Tim's novel reminded him of the Dortmunder books by the late Donald Westlake.

Here we are holding Tim Hallinan's 'In Fields Where They Lay', a Christmas crime tale that Tim graciously sent us autographed copies of. It was to be our final shared read. Dad always enjoyed a good killing, and he said Tim's novel reminded him of the Dortmunder books by the late Donald Westlake.Dee’s process with her mother is not my process. There is less laughter and more uncomfortable conversation. Dee didn’t have those years of prior discussion to let her work through her own emotions about losing a parent, much less to face the harsh reality of her parent choosing to die weeks or months earlier than a natural death might occur.

Unbeknownst to me until almost the end of my writing, my earliest crime-writing mentor was working through dying discussions with her family. Another friend was also struggling with a terminal diagnosis; she and her daughters spoke extensively of the option for assisted dying. Their processes are not Dee’s either. Dee’s mother lives three provinces away and the brutal fact of her impending death doesn’t hit home until she arrives in a wheelchair, with a nurse-attendant, and towing an extra suitcase filled not with Christmas presents but with medical supplies and comfort items. You can imagine the shock.

This theme winds from the earliest pages through to the last: how do you face death - a parent’s dying too young or a child dying before its parent, and what are the emotional, psychological, legal, and societal obstacles to one’s ability to access a ‘good death’ in the manner of their choosing?

I’ve tried not to let that one theme take over the book. It is, after all, a crime novel, with a dead body on Page One and several suspects – some of whom are red herrings – all weaving their own tales through a wintery western Alberta landscape.

But via the characters named above and the secondary characters who come and go through the pages, we see perspectives from dying people, their family members, medical and religious individuals, as well as touching on differing attitudes to MAID across Canada and across age groups.

All of those perspectives flowed freely to me as soon as I showed willing to listen to people – friends and strangers alike – confide their hopes and concerns about end-of-life issues. I was surprised to find that acceptance of assisted dying is far higher than politicians seem to believe. Almost everyone knew of someone who had lingered far longer than they would have wished. Many had walked a friend or relative along that path. Most spoke of wanting the law made more flexible, not less. There was strong support for a change to allow for advance directives; people wanted the option available to them even – or especially – if they were not mentally competent to consent to the medical procedure when the time came. There is more work ahead for governments and communities and families to integrate this new option into the medical and social frameworks of our nation.

To learn more about Medical Assistance in Dying - the state of the law, and the stories of those who have walked loved ones on that path,see Dying With Dignity Canada

My father? He didn’t live to see the book published. In

fact, he died a few short weeks after our last Christmas together, only a few

months after I’d written Dee’s final Christmas

Day with her mother.

His application went smoothly thanks to support from local

Dying With Dignity volunteers and a devoted medical team who helped him with

the paperwork, guarded his dignity well, and provided all the comforts possible

during his last weeks of life. He went out happy, with a joke on his lips.

I believe he, who taught me to enjoy books almost as soon as I could wrap my tiny fingers around one, would have been pleased with the way this book turned out. I raise a glass of his favourite ginger wine to his memory each Christmas.

I believe he, who taught me to enjoy books almost as soon as I could wrap my tiny fingers around one, would have been pleased with the way this book turned out. I raise a glass of his favourite ginger wine to his memory each Christmas.

No comments:

Post a Comment